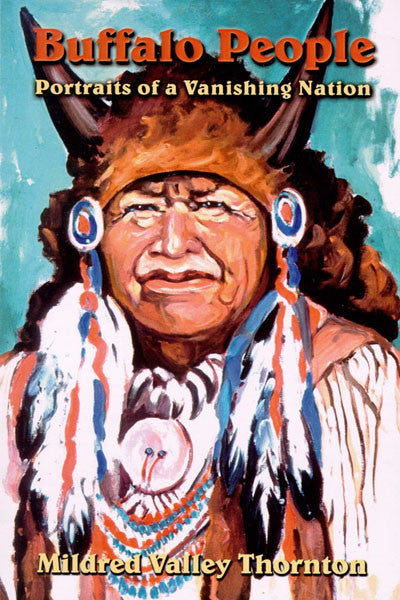

Buffalo People: portraits of a vanishing nation

By: Thornton, Mildred Valley

ISBN: 0-88839-479-9

Binding: Trade Paper

Size: 8.5" X 5.5"

Pages: 208

Photos: 127

Illustrations: 38

Publication Date: 2000

PR Highlights: An artist's look at the Plains Indian Culture

PHOTO Highlights: 68 color plates of MV Thornton oil paintings

Description: The author shares not only her artistic rendition of the prominent natives she paints, but stories, legends and personal experiences of these historical figures of a vanishing nation. Mildred Valley Thornton had an abiding passion which she pursued with almost missionary fever throughout her life - the preservation of Plains Indian culture. For over fifty years she dedicated herself to that purpose through the medium of her paintings, writing and lectures. During the course of her self-appointed career, Mildred not only painted the portraits of many prominent and historical Natives, most of whom are long since dead, but she assembled an accompanying catalog of anecdotes, folklore and legends, mostly related in now long forgotten native tongues, which today provide a unique chronicle of a vanished age. This publication is a unique collection of both colorful portraits and the fascinating story behind each one.

Author Biography:

Born of a large farming family in the small Ontario town of Dresden at the beginning of the last decade of the nineteenth century, the young Mildred Stinson soon demonstrated to her parents that she was not destined to remain on the farm. They recognized her artistic abilities and sent her to study at Olivet College in Michigan, from which she graduated in 1910. She continued her studies at the Ontario School of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago before the lure of Canada’s burgeoning prairie beckoned her west. Arriving in Regina, Saskatchewan, with little more than a valise and her paintbox, she immediately fell under the spell of the vast, limitless plains and, even more avidly, developed a lasting fascination for the then nomadic Indian tribes who inhabited that immense solitude. It was then and there that she commenced her life’s work to preserve on canvas and in the written word the countenances and culture of what she perceived to be a threatened and fascinating society. In 1915 she married John Henry Thornton, some five years her senior, who had immigrated from Sheffield, England and operated a thriving business in the growing prairie town. The partnership was a long and happy one and, though John Henry was a man of few words and infinite patience, he became what would be known today as a devoted “support system” to his young wife’s endeavors. This was perhaps best exemplified by a brief paragraph on the fly-page of her book Indian Lives and Legends (1967) which stated: “This book is dedicated to the memory of my husband, John H. Thornton, whose patience, encouragement and co-operation made this whole project possible.” By then her husband had been dead for nearly ten years. A decade after her marriage she gave birth to twin boys in Toronto and they were largely brought up by their father owing to their mother’s frequent absences from home. Mildred would embark on extended sketching trips for weeks at a time, living with the Indians in their camps and tepees, painting their portraits and recording their legends. Her energy and single-minded focus was tenacious. Suspicious at first, the Indians gradually came to

accept and trust her and she became privy to many ceremonies and rituals that few non-Indians have been privileged to witness. Upon occasion she took her sons with her much to their excitement

and fascination. For long periods the only “whites” whom she would encounter would be the RCMP constable, the Indian agent and the missionary clergy. Though her primary interest was to paint the Indians she was also an accomplished landscape artist, in both oil and watercolour, and her works became much in demand. Her style was frequently described as “majestic, powerful and bold.” Vivid colour, particularly in her watercolours, became an earmark of her work. She was tremendously prolific and was often compared to her near-contemporary, Emily Carr, much to her annoyance, and frequently identified with the Group of Seven. It was her Indian portraiture, however, that became her life’s obsession. She came to refer to the ever-growing number of paintings as “The Collection” and, as such, they became quite

inviolable. She refused all offers to sell the paintings individually. An abiding patriot, it was her ambition to hand this priceless legacy of Canada’s native history intact to the Government of Canada, the only custodian that she would accept. As the Collection became more famous she refused generous offers

from the UK, USA and Germany. The Collection was a unique assemblage, depicting Canada’s aboriginal peoples and its constituent parts, and they were often the only graphic record of events in existence.