Shaheen: a falconer's journal from Turkey

Details

By: Jones, Paul H.

ISBN: 978-0-88839-638-9

Binding: Trade Cloth

Size: 8.5" X 5.5"

Pages: 160

Photos: 0

Illustrations: 32

Publication Date: 2007

Description

PR Highlights: Non-fiction; A man and his falcon. (Turkey 1970s).

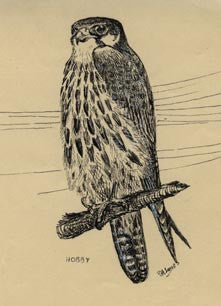

PHOTO Highlights: Over 30 original illustrations by author

Table of Contents

Description: The book chronicles the capture and 'taming' of a tiercel saker falcon. While the story details the training and hunting episodes that took place with the bird, it is really a study of the bond that can grow between falconer and falcon.

A lyrical account of an association between a man and a bird against the exotic backdrop of the Turkish countryside. The book chronicles the capture and taming of a tiercel saker falcon. While the story details the training and hunting episodes that took place with the bird, it is really a study of the bond that can grow between falconer and falcon. Shaheen is a naturalist's account of an association between author Paul Jones and a saker falcon in the early 1970s, before the scourge of DDT affected many species of falcons throughout the world. The author/illustrator gives us an inside view of falconry and all its trappings, little changed since the Middle Ages. In this narrative, taken from his own diaries, Jones skillfully describes his efforts to hunt game in scattered locations throughout Turkey-its dry zones, its mountains and its frozen wastes. Though there were many losses of Shaheen during the hunt, the two always reunited. In the end, in striving to find a mate for his tiercel, Jones loses the newly caught falcon and ends up releasing Shaheen, his hunting companion for a year and a half. The book begins with a brief introduction to the history and geography of the region where the story takes place. The first section of the book is entitled Coming In and is made up of five chapters. Chapters one through five cover the author's experiences in the region, first sight of the eyrie from where Shaheen is obtained, the actual capture of the bird, starting training and getting the bird entered. The second section of the book is called Going Up and is again comprised of five chapters. These chapters are descriptions of various training and hunting episodes with Shaheen. The third section of the book is called Staying Out and is made up of four chapters. These chapters detail further experiences with Shaheen, the search for a suitable mate for him, the loss of the new mate, Shaheen's own disappearance and reappearance and a final farewell to the bird. The book concludes with an epilogue and a couple of appendices: Appendix I presents the first molt feather measurements. Appendix II offers readers a selection of excerpts from notable falconry books in Jones' possession and add some interesting independent observations to those of his own work about this fascinating falcon of the old world. They deal with descriptions of the birds, their observed behaviors and their usefulness for falconry. Additionally, Jones' delightful illustrations accompany the text throughout the book. This book is certain to entertain falconers and those unfamiliar with the art of falconry alike. Aside from the brief accounts of saker falcons being used for falconry that appear in Middle-Eastern literature, little is known of this desert falcon and its hunting habits. This is a valuable addition to that body of literature.

Author Biography

He has been a member of the British Columbia Falconry Association and belongs to a long list of British Columbia birding and natural history organizations. Jones has been a life member of the Bombay Natural History Society since 1948 and is presently Chair, Friends of Caren. His previous works include The Marbled Murrelets of the Caren Range and Middlepoint Bight, Western Canada Wilderness Committee, 2001, and Nature's Anniversary, Seabird Press, 2004. He has also written many articles of natural history interest in the Vancouver Natural History Society's publication, Discovery, and has published in BC Naturalist (and served as editor of) the quarterly of the Federation of BC Naturalists.

Book Reviews

The Falconer Journal

2008, pg 112

Review by John Loft

University of Nottingham-School of Geography

In the hardback book of 158 pages, the Canadian author gives us an autobiographical account of the four years ('67-71') he spent in Ankara, Turkey, Working for the U.N., in which time he took a sakret from a rock eyrie and kept it through one moult until his leaving the country forced him to whistle it down the wind. The title indicates that the record of events is based on a diary, as it was bound to be after an interval of nearly forty years. The narrative moves through a series of episodes, exciting, amusing, informative, or even rather dull, but allrelated with relish. Jones must have recorded every last detail of his dealings with the sakret or else have an astonishing memory but, either way, he is able to rediscover his own past in a convincing way that enables anly interested reader to share in some measure the experience of the iunfamiliar world. Turkey's people, landscapes, customs, history, and way of life are sketched in as a necessary background to the sakret's brief story. It would be a sad book without it. (A map showing all the places with strange names that he visited would have been a help, though). Happily, he holds my interest. It is not a book that is easy to put down. The two dozen or so pen-and-ink illustrations, not all of birds, were drawn by the author. He seems to be a competent draughtsman and the best of his sketches deftly catch a falcon's looks and poses but the worst of them should have been left out. I ought to explain at the early stage that shaheen is the Turkish word for falcon so that the reader will understand the strange choice of title for a book about a sakret, and after that I must let any falconer reader know that the sakret was the author's one-and-only hawk ever, apart from an eyass saker that was lost after a month when she broke free, having been put to weather, unmanned, on a creance that gave her fifteen yards to move in. You're quite right: it's a chapter of mistakes as well as accidents. The eyass, fresh from the eyrie, was at first kept loose on an adequate aviary and gradually persuaded a step to the fist for food, at which stage Jones took his annual holiday. On his return, equipped now with a hood and some information, he continued with his unorthodox system of training, which I shall not particularize but skip at once to the time when, by generally doing the opposite of what the books advised, he arrived at the stage of calling it to the lure. It just shows what imagination, application, and patience can do. For its first free flight it was thrown off impulsively at a flock of linnets passing twenty yards upwind. The sakret disappeared over the brow five hundred yards away downwind. After the panic it returned from 2,000 feet. The story thereafter records many similar occasions when the hawk was thrown off at a venture or allowed to take off in its own time. The author deserves all credit for persistently trying to find quarry and catch it. The amazing thing is that, being loosed so often and allowed so much aimless liberty, the sakret was recovered, again and again, sometimes at considerable distance from the point of loss. It was out for a total of 35 nights in one season, and not always in the same area. Jones believed that it was killing for itself. Strangely, he never tells us how, or if, he controlled the amounts of meat he fed it. If you would like to ponder the reasons for the boomerang qualities of the eyass of the saker species, read the book. The very first sentence will rock you back: Not much is known of the saker falcon and little has been written about its usefulness for falconry. What? But pause a moment. In the 1960's that was a fair comment. Yet in ignoring the passage of time lies the chief defect of the book. Then, there was room for a book that introduced falconry to a public that was mostly ignorant about it, but there isn't now. Then, Jones could justifiably have been pleased with, even proud of, his achievement, but now he should have learnt what can be done and how it should be done, so that the only way now open to him was to write apologetically (but the only mistake he admits is the one he made in losing the saker) or to emphasize that he is writing about times past and how different they were.